Introduction. The development of the rumen is critical to successful weaning and good growth rates after weaning. The changes that take place in the rumen around weaning are interesting, complicated, and not yet fully understood. This Calf Note is designed as an introduction to the factors influencing rumen development in calves.

Factors Required for Rumen Development. There are five “ingredients” that are required to cause ruminal development. They are:

- Establishment of bacteria in the rumen

- Liquid in the rumen

- Outflow of material from the rumen (muscular action)

- Absorptive ability of the tissue

- Substrate available in the rumen

A number of other metabolic changes occur during ruminal development in the rumen and other tissues, but we will consider the above “ingredients” as requisite for the rumen to begin to function.

Bacteria. When the calf is first born, the rumen is sterile – there are no bacteria present. However, by one day of age, a large concentration of bacteria can be found – mostly aerobic (or oxygen-using) bacteria. Thereafter, the numbers and types of bacteria change as dry feed intake occurs and the substrate available for fermentation changes. The numbers of total bacteria (per ml of rumen fluid) do not change dramatically, but the types of bacteria change as the calf begins to consume dry feed. This results in a dramatic loss of aerobes and predominance of anaerobes with increasing dry feed intake. Many methanogens (methane producers), proteolytic (protein degraders), and cellulolytic (cellulose degraders) become established. The number of “typical” rumen bacteria – those found in adults – become established by about two weeks after dry feed intake commences.

Liquid in the Rumen. To ferment substrate (grain and hay), rumen bacteria must live in a water environment. Without sufficient water, bacteria cannot grow, and ruminal development is slowed. Most of the water that enters the rumen comes from free water intake. If water is offered to calves from an early age, this is not usually a problem; unfortunately, many producers in the U.S. do not provide free water to their calves until calves reach 4 or more weeks of age.

Milk or milk replacer does not constitute “free water”. When milk or milk replacer is fed to calves, it by-passes the rumen and reticulum by the action of the esophageal groove. The esophageal (or reticular) groove is active in the calf until about 12 weeks of age. The groove closes in response to nervous stimulation, shunting milk past the reticulorumen and into the abomasum. Closure of the groove occurs whether calves are fed from buckets or bottles. Therefore, the feeding of milk replacer should not be construed as providing “enough water”. Feeding water can increase body weight gain, starter intake, and reduce scours scores.

Outflow of Material from the Rumen. Proper ruminal development requires that material entering the rumen must be able to leave it. Measures of ruminal activity include rumen contractions, rumen pressure, and regurgitation (cud chewing). At birth, the rumen has little muscular activity, and few rumen contractions can be measured. Similarly, no regurgitation occurs in the first week or so of life. With increasing intake of dry feed, rumen contractions begin. When calves are fed milk, hay, and grain from shortly after birth, normal rumen contractions can be measured as early as 3 weeks of age. However, when calves are fed only milk, normal rumen contractions may not be measurable for extended periods. Cud chewing has been observed as early as 7 days of age, and may not be related to ruminal development per se. However, calves will ruminate for increasing periods when dry feed (particularly hay) is fed.

Absorptive Ability of the Rumen Tissue. The absorption of end-products of fermentation is an important criterion of ruminal development. The end-products of fermentation, particularly the volatile fatty acids (VFA; acetate, propionate, and butyrate) are absorbed into the rumen epithelium, where propionate and butyrate are metabolized in mature ruminants. Then, the VFA or end-products of metabolism (lactate and ß-hydroxybutyrate) are transported to the blood for use as energy substrates. However, there is little or no absorption or metabolism of VFA in neonatal calves. Therefore, the rumen must develop this ability prior to weaning.

The rumen wall consists of two layers – the epithelial and muscular layers. Each layer has its own function and develops as a result of different stimuli. The muscle layer lies on the exterior of the rumen and provides support for the interior (epithelial layer). Its primary role is to contract to move the ruminal contents around in the rumen and move digesta into the omasum. The epithelial layer is the absorptive layer of tissue that is inside the rumen and is in contact with the rumen contents. It is composed of a very thin film of tissue holding many small finger-like projections called papillae. These papillae provide the absorptive surface for the rumen. At birth, the papillae are small and non-functional. They absorb very little and do not metabolize significant VFA.

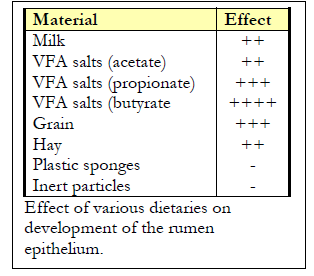

Many researchers have evaluated the effect of various compounds on the development of the epithelial tissue – in relation to size and number of papillae and their ability to absorb and metabolize VFA. The results (Figure) indicate that the primary stimulus to development of the epithelium are VFA – particularly propionate and butyrate. Milk, hay, and grain added to the rumen are all fermented by the resident bacteria to these organisms; therefore, they contribute VFA for epithelial development. Plastic sponges and inert particles – both added to the rumen to provide “scratch” – did not promote development of the epithelium. These objects could not be fermented to VFA, and thus did not contribute any VFA to the rumen environment. Therefore, rumen development (defined as the development of the epithelium) is primarily controlled by chemical, not physical means. This is further support for the hypothesis that ruminal development is primarily driven by the availability of dry feed, but particularly starter, in the rumen.

Availability of Substrate. We have seen that bacteria, liquid, rumen motility, and absorptive ability are established prior to rumen development, or develop rapidly when the calf begins to consume dry feed. Thus, the primary factor determining ruminal development is dry feed intake. To promote early rumen development and allow early weaning, the key factor is early consumption of a diet to promote growth of the ruminal epithelium and ruminal motility. Because grains provide fermentable carbohydrates that are fermented to propionate and butyrate, they are a good choice to ensure early rumen development. On the other hand, the structural carbohydrate of forages tend to be fermented to a greater extent to acetate, which is less stimulatory to ruminal development. Early and aggressive intake of calf starter is the key to good ruminal development. Offer starter from 3 days of age and keep it fresh, clean, and available. This will help provide the proper stimulation for rumen development and allow early weaning.