Click here for a PDF version of this Calf Note

Introduction

In a series of three abstracts presented at the 2014 Joint Annual Meeting of ADSA, ASAS and other scientific societies, Dr. Kim Morrill and co-workers presented some interesting data related to management of Jersey cows and newborn Jersey calves. This Calf Note will review the first of these abstracts, related to the management of colostrum on Jersey farms in New York and Vermont.

Abstract #1 – Colostrum Management on Jersey Farms in New York and Vermont

A questionnaire related to colostrum management practices was mailed to 75 Jersey farms in NY and VT; a total of 38 producers responded with a completed survey. The farms ranged in size from <50 cows (14 farms) to >2,000 cows (1 farm). Most farms (67% of respondents) has £100 cows.

The authors (Morrill, Spring and Tyler) reported multiple categories of herd sizes. For sake of simplicity, I’ve combined some of the categories reported by the authors. Further, I’ve omitted some of the questions for the sake of focusing in on some key management practices. We’ll look at a few of the key results broken into Small (£100 cows) or Large (>100 cows) herds.

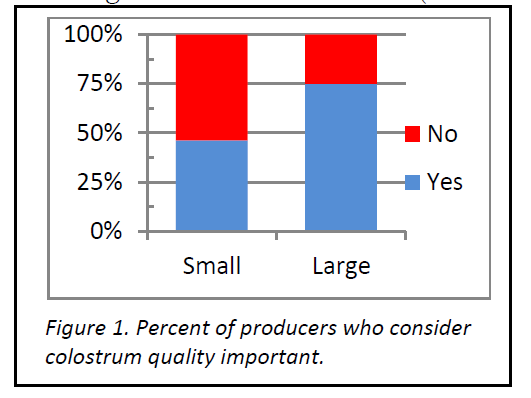

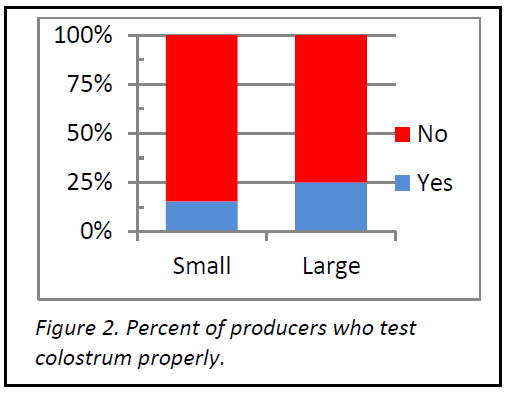

The producers were asked if colostrum quality was a concern on their operations. Figure 1 shows that a greater portion of large producers consider colostrum quality an important criteria for calf health. Small producers were also much less likely to test (or test properly) colostrum for quality. Only five producers reported using either the colostrometer or refractometer to evaluate colostrum quality on the farm (Figure 2). Considering the importance of colostrum to the newborn and the huge body of data that shows that 1st milking colostrum is inherently variable even from older cows, it’s somewhat disconcerting that so few producers took the time to conduct this simple but essential test when colostrum is collected. Note – the research data allowed producers to report different methods of evaluating colostrum quality – volume produced, color and consistency. However, none of these methods can accurately indicate colostral IgG concentration, which is the most important reason to feed high quality colostrum.

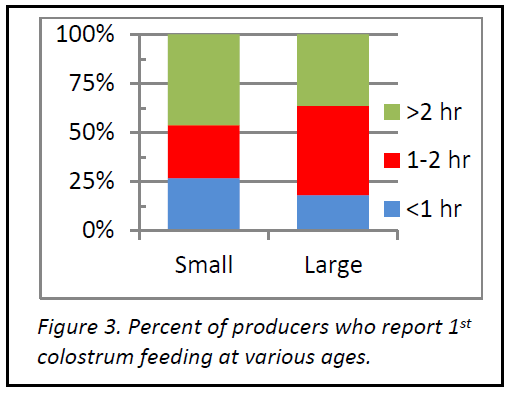

One of the keys to successful passive transfer is ingestion of colostrum at an early enough age to maximize absorption of ingested IgG. Calves should be fed colostrum as soon as possible, but certainly within 2 hr of birth (preferably within an hour of birth). The age at which producers report regularly feeding their calves is in Figure 3. Over 50% of producers (both Small and Large) reported feeding calves at <2 hr of age, which is in line with current recommendations. However, only about ¼ of these producers routinely tried to feed calves within the 1st hour of life.

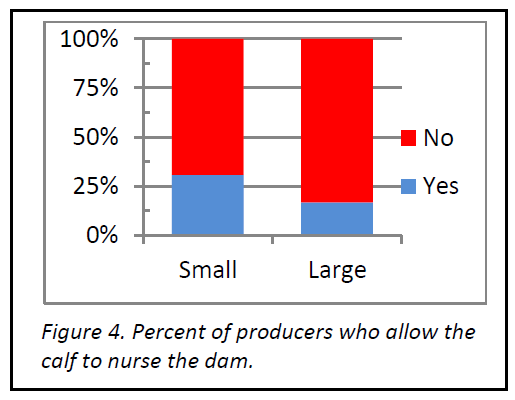

Allowing calves to nurse the dam is almost always a bad idea. Calves left to nurse the dam usually consume less colostrum, consume it later and are predisposed to greater incidence of disease – not only because they

consume less colostrum, but they’re also more likely to be exposed to a greater number of pathogens by remaining with the dam (and potentially other cows if group maternity housing is used). Thus, few calf advisers recommend that the calf remain with the dam for more than a few minutes. The risk of disease transmission is far greater than welfare benefits to either the cow or calf. However, a significant portion of Jersey producers reported allowing the calf to nurse the dam (Figure 4). This was particularly true of the smaller producers, where >25% of them allowed the calf to nurse.

Eleven producers (29% of respondents) reported using a commercial colostrum replacer. Although not specifically asked as part of the survey, we can infer from the results that few or none of the producers use a commercial product as the sole source of IgG; rather, these products are primarily used to complement the maternal colostrum program and replace colostrum when it is poor quality or unavailable. Only two producers reported pooling colostrum. Considerable research suggests that when colostrum is pooled, the amount of contamination increases dramatically and, therefore, pooling is not recommended, even as a means of “standardizing” colostrum IgG concentration across multiple cows.

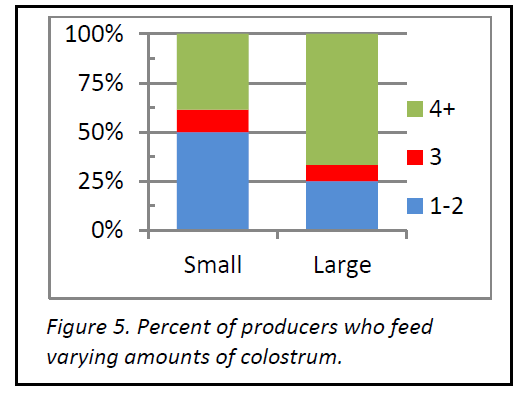

In addition to quality of colostrum, the quantity fed is critical to ensuring adequate passive immunity. Generally, calves should receive at least 4 L of maternal colostrum in the 1st 24 hours of life. Even small Jersey calves benefit from the nutrition and immune components of colostrum. In this study, the authors report that about 60% of small producers fed <4 quarts to their calves. This was quite a bit different with larger herds, where a great majority of producers report feeding at least 4 quarts in the first 24 hr.

Perhaps the most concerning statistic reported by the authors was that only 1 producer reported routinely monitoring serum for rate of passive transfer. This small percentage (1 / 38 = 2.6% of producers) indicates that (1) the process of collecting blood and monitoring serum total protein remains a challenging management practice and (2) producers need to be educated on the need to measure and manage this important critical control point in the overall colostrum management program. The ONLY way to know whether the colostrum management and feeding program is successful is to routinely monitor serum IgG or total protein in calves after 24 hr of age. It’s unfortunately that so few producers recognize and commit to routine monitoring.

This interesting research provides us important information on the current status of colostrum programs in the Northeast U.S. and shows that improvements are still needed in colostrum management on Jersey farms. Producers have learned that volume, quality and timing of colostrum feeding are important, but likely need further assistance in actual implementation on the farm.

Reference

Morrill, K. M., M. M. Spring, and H. D. Tyler. 2014. Current colostrum management practices on Jersey farms in Vermont and New York State. J. Dairy Sci. Vol. 97, E-Suppl. P. 419.