Introduction

Newborn calves are more sensitive to cold temperatures than mature ruminants and early in life, the lack of a body fat stores, and a functional rumen makes calves more susceptible to cold. Calf raisers often use deep straw bedding, calf jackets or heat lamps to help calves maintain their body temperatures during cold weather. But, while we try to assist the calf to maintain body temperature, what do calves prefer? A cooler or warmer hutch? An article in the January 2025 issue of the Journal of Dairy Science evaluated the preference of calves for warmer versus colder hutches during winter. The study was designed to determine if calves preferred warmer vs. cooler hutches by the inclusion of different number of heat lamps with one of four hutches the calves could choose.

The Research

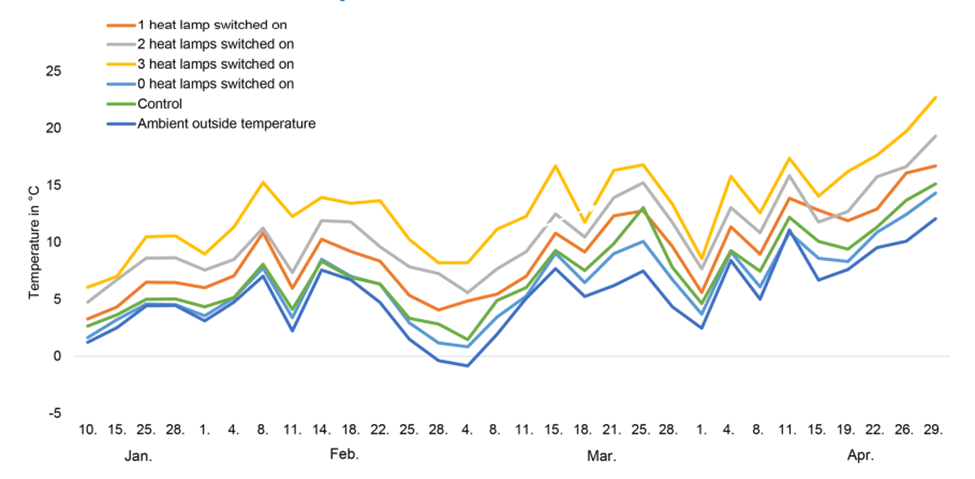

The study was conducted on a dairy farm in northeast Germany from January to April 2022. Ambient temperatures during the study ranged from -7.3 to 21.8°C (19 to 71°F) with an average of 5.4°C.

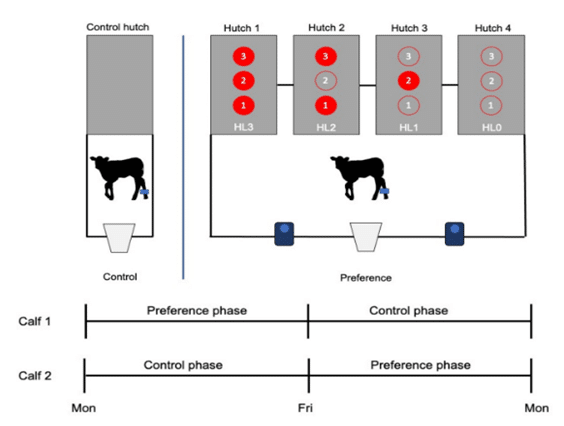

Holstein–Friesian calves (n = 32) were born on a dairy farm in Germany and were removed immediately from the dam. Calves were fed 4 L of colostrum and were housed in an individual hutch during the control periods. During the preference testing period, calves were moved into a separate area which contained four different hutches, each with either 0, 1, 2 or 3 heat lamps (250 W, located 1 m from the floor) illuminated. Figure 1 shows the general outline of housing for the experiment. Calves were housed in control hutch (monitored for 3 to 4 days) and moved to the preference area for behavioral evaluation (3 to 4 days). The researchers used accelerometers and video cameras to determine the calf’s location and posture. The study was conducted during the first week of life.

All hutches were maintained with clean, deep straw bedding (nesting score = 3) and calves were fed 7 L of whole milk twice per day (yes, 14 L/day) as well as water, grain and dry hay. No information was available for composition of the feeds offered during the study. The authors did not report if all milk was consumed.

The Results

Each heat lamp increased the inside temperature by 2.6°C. The temperature curves from the different hutches during the preference phase are in Figure 2.

Calves exhibited no preference for any of the preference hutches. They spent 90% of their time inside a hutch and 80% of their time lying down. The lack of preference may have been due to the increase in temperature in hutches with 2 or 3 lamps illuminated. The increase in temperature in the hutch with 3 lamps illuminated was 6.6°C, and when the average daily temperature was sufficiently high, the hutch may have been too warm, and the calves avoided it.

Other research (Borderas et al., 2009) reported that newborn calves (1 to 3 days of age) did prefer heated environments (with heat lamps), and this effect was independent of amount of milk fed (8% vs. 30% of BW). Calves spent more time in the warmer zone of the hutch (nearer the heat lamp). It should be noted that, although calves were offered 8 or 30% of BW (average of 13 L/d), calves consumed an average of 3.6, 6.2 and 7.9 L/d during days 1 to 3. This equates to an average of 14% of BW. Calves fed the low quantity of milk consumed 2.8, 3, and 3 L/d. Thus, the difference in milk consumed was smaller than the experimental design due to feed refusals. During this study, mean daily temperature was 3.7°C (39°F), which is definitely lower than the calves’ lower critical temperature (LCT, the lower end of the thermoneutral zone).

That calves in the study of Sonntag were fed 14 L of whole milk per day makes this research somewhat unique. The authors did not report any milk refusals, which differs from the research of Borderas et al. (2009). We know that heat of digestion and production of heat by calves depends on amount of milk consumed. Calf Note #249 discusses the effects of volume of milk consumed and heat produced by the calf. More milk ingested equals more heat produced. Thus, these calves likely were generating sufficient internal heat so that, along with deep straw bedding, they were sufficiently warm so that they never (or rarely) were outside of their thermoneutral zone. Remember, the LCT depends not only on the ambient temperature, but also on the heat generated by the calf and insulative capacity of the calf’s hair coat and bedding. With the limited data available from the manuscript, it’s impossible to estimate the LCT of the animals, but without a doubt, it was lower than would be expected for similar calves fed a lower milk ration.

Summary

Though an interesting article, the results of this study are difficult to apply to other parts of the world where lower amounts of milk are normally fed (especially to week-old calves) and average daily temperatures are colder. If we assume that it’s likely that calves in this study were always within their thermoneutral zones due to heat produced by digestion of milk and sufficient “nesting”, the data suggest that calves cannot discern differences among heated hutches or have no preference for one heated hutch over another. A follow up study with calves housed in colder weather and fed less milk (14 L/d for week-old calves is not an industry standard in most parts of the world) would be instructive.

References

Borderas, F. T., A. M. B. de Passillé, and J. Rushen. 2009. Temperature preferences and feed level of the newborn dairy calf. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 120:56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2009.04 .010.

Sonntag, N., F. Sutter, S. Borchardt, J. L. Plenio, and W. Heuwieser. 2025. Temperature preferences of dairy calves for heated calf hutches during winter in temperate climate. J. Dairy Sci. TBC. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2024-25271

.